A Gerrymandering Comeback in California … via Arizona?

Several months of quiet whispers have quickly turned into a resounding buzz -- and a nervous buzz, no less -- about a case pending before the U.S. Supreme Court that questions whether it's constitutional for independent state commissions to have the sole power to draw political district maps.

The case is centered on Arizona, but the buzz being heard on this side of the Colorado River arises from the fear that if a lower court's ruling is thrown out, California may very well be next in the return to partisan congressional gerrymandering.

It explains why everyone from legal scholars to three former California governors is asking to be heard before the nation's highest court.

The case in question is Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, now scheduled to be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in March. And the argument being made by Arizona's legislative leaders in their quest to outlaw the state's redistricting commission is pretty simple: The U.S. Constitution, they say, vests all power over congressional elections in state legislatures -- and no one else.

The legal fight has been brewing for a long time. Arizona voters approved a ballot initiative in 2000 that created an independent redistricting commission. A decade later,California voters assigned the drawing of congressional districts to a similar panel (after giving the panel the power to draw legislative districts in 2008).

Californians Speak Out

Now, a swarm of Californians are filing amici curiae briefs on behalf of the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, clearly fearing that the fate of the California Citizens Redistricting Commission depends on what happens in Washington, D.C., before the end of 2015.

While California's commissioners have filed their own amicus brief in support of the Arizona panel, their fight was joined on Friday by a similar brief from three former California governors -- George Deukmejian, Pete Wilson and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Of those, Schwarzenegger has the most to lose in terms of his legacy, as he was a driving force behind the two initiatives that wrestled control of political map drawing away from the Legislature.

The governors were joined in their filing by the California Chamber of Commerce as well as wealthy activists Charles Munger Jr. and Bill Mundell -- two big money backers of the redistricting initiatives.

It's fascinating that the California cavalry is rushing in to defend its Arizona compatriots now, given that this effort to kill Arizona's redistricting commission is pretty much down to its last swing of the bat. A U.S. District Court ruled against Arizona's legislative leaders last February, and it's not exactly clear that the Supreme Court justices will even consider all of the arguments made by legislators seeking to regain their redistricting power. Perhaps, but everyone still sees the stakes as high.

"The Arizona litigation," said California Chamber of Commerce President Allan Zaremberg, "jeopardizes the will of the California electorate and its embrace of fair redistricting and competitive elections."

Who Can 'Legislate'?

For the average observer, the crux of the case may be this: Is the power of Arizona voters to write legislation -- legislation written through the ballot initiative process -- equivalent to the legislative power over elections in Article I, Section IV of the Constitution:

The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.

Arizona's legislative leaders say, quite simply: no way. In their December filing with the U.S. Supreme Court, they argue the above passage is crystal clear:

"The term 'the Legislature' is clear and explicit and has an unambiguous meaning repeatedly recognized by the Framers and this Court: the representative lawmaking body of a State. In the Constitution, the Framers carefully assigned particular obligations to particular State-level entities, whether the 'people,' the 'legislature,' the 'executive,' or the 'State' generally. That precise division of labor leaves no doubt that they intended that 'the Legislature' -- meaning the representative lawmaking body -- be the entity that 'prescribe[s]...Regulations governing redistricting."

It's worth noting that Arizona's independent redistricting commission is selected by a different process than the one in California, though Golden State activists and lawmakers may have used parts of the Arizona process to help shape the final details that were drafted in 2007.

In Arizona, the independent commission has five members. Four of them are chosen by the state's legislative leaders from a pool vetted by a judicial commission; the chairperson of the commission is then selected (out of the remaining applicants) by the four commissioners.

In California, the panel is 14 members. Eight commissioners are chosen at random, from a pool of applicants vetted by the state auditor but from which each of the four legislative leaders is able to reject six names. Those eight commissioners then choose six colleagues from the remaining applicants.

If Arizona's System Is Struck Down ...

From a layman's perspective, if Arizona legislators are successful in convincing the Supreme Court that they been stripped of their right to have a role in crafting congressional maps -- even though the Arizona system allows top lawmakers to pick four-fifths of the commission -- then it would seem much easier for California's legislators, who have a much smaller role, to argue they, too, have been wronged. Remember, the entire political campaign was about stripping politicians of their power to draw congressional districts.

(And in case you're confused, the pending Supreme Court case is only about drawing congressional districts, not those for Arizona's Legislature.)

Most states across the nation continue to have their political maps drawn by legislators -- a power that's led to countless charges of districts skewed by gerrymandering for partisan gain. And that's what supporters of independent redistricting say will happen again if the high court strips the Arizona commission of its power to craft the state's nine congressional districts.

"The Arizona Legislature's lawsuit is just an effort to get the foxes back in the henhouse," said Kathay Feng, executive director of California Common Cause and one of the authors of the California redistricting laws.

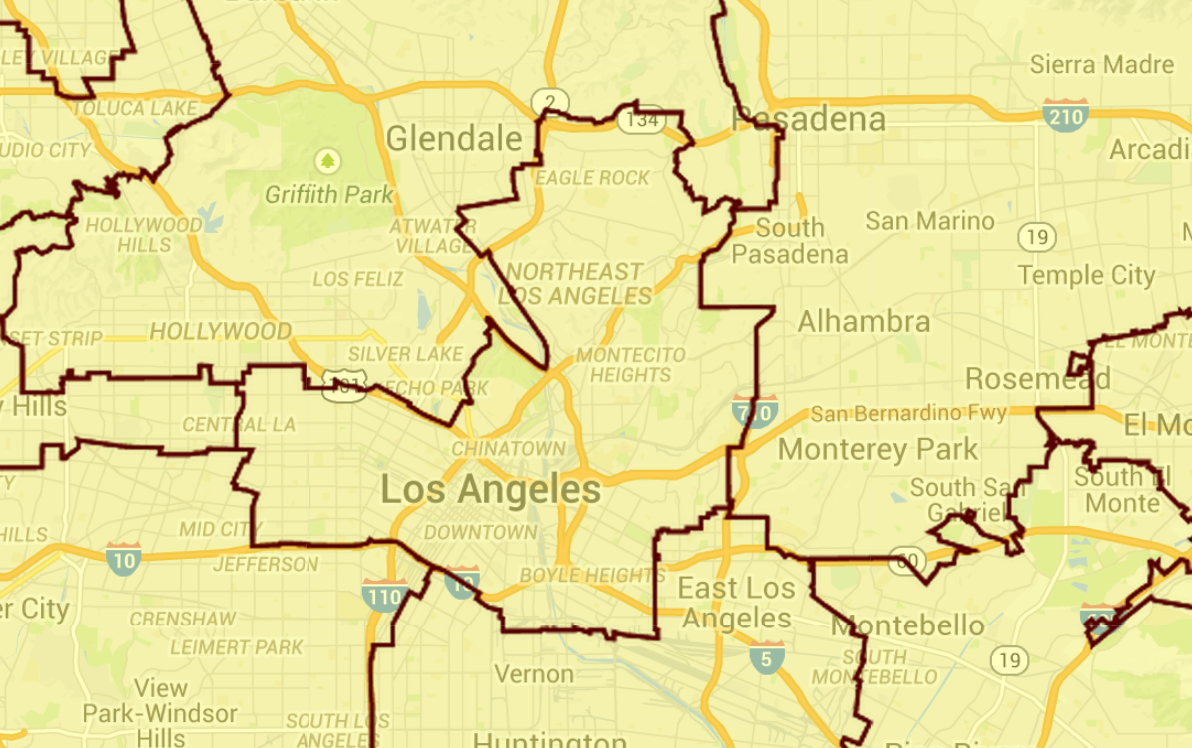

In California, a redistricting process dominated by majority Democrats in the Legislature would undoubtedly produce more Democrats and fewer Republicans in the state's congressional delegation, though leaders of both parties in the state Capitol opted for a map that protected incumbents in 2001, the final once-in-a-decade redrawing before the independent commission took over.

Even some members of Congress don't want to go back.

“Districts drawn by incumbents to protect their jobs makes politicians less accountable to their constituents," says Rep. Julia Brownley, a Ventura County Democrat. She and 19 other incumbents filed their own amicus brief in hopes of blocking the rollback effort by legislators in Arizona.