China and the Art Of Deal

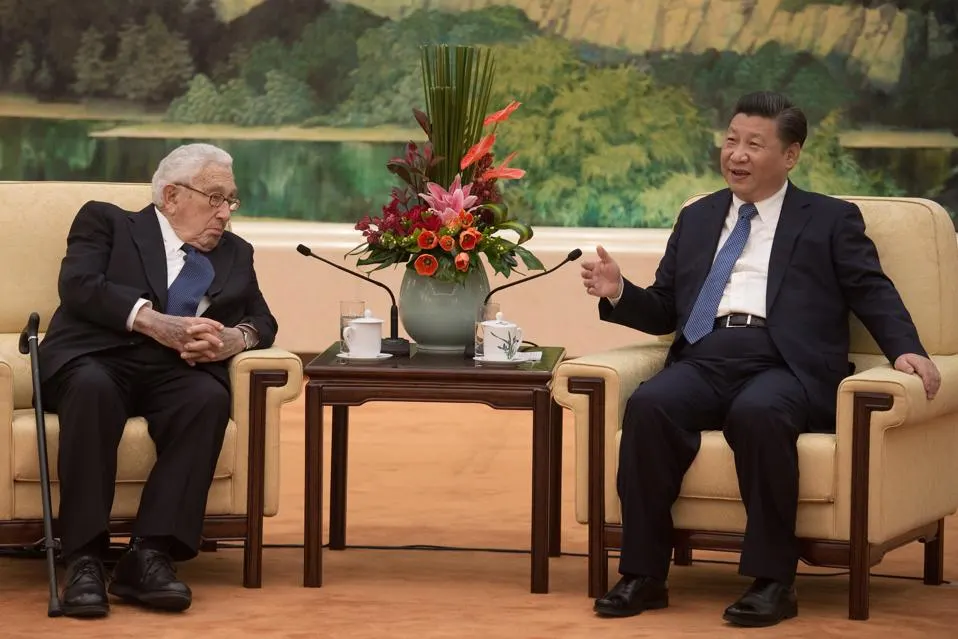

During a recent interview for our forthcoming documentary on the U.S.-China relationship, Henry Kissinger, the 56th Secretary of State, said: "If we [the United States and China] were to clash, it would be a disaster for the whole world. So the relationship is an exploration of our necessities. And it is an effort to make the Better Angels of our nature dominate amidst a maelstrom of events."

Those lofty ideals are plainly needed today, especially at a time when we face new Cold War realities with Russia. They also happen to be constricted by persistently negative U.S. public opinion about China, driven in large part today, as Trump's campaign successfully highlighted, by jobs lost to China.

But what if U.S. sentiment towards China could be changed now through a policy that settled the score--returned solid middle-class jobs to America even before the wave of middle-class Chinese become the natural buyers for our goods and services over the next 5-10 years? What if such a policy would also reduce our treasury debt to China, replacing it with longer-term equity (or quasi equity) and also made a significant dent in our infrastructure deficit?

It turns out this policy could very well prove to be in China's financial interest. Perhaps all that is needed is a master dealmaker to put it together.

China has built up an astounding mountain of monetary reserves, a large portion of which is comprised of U.S. government securities. But this Chinese capital faces a specific dilemma in today's loose monetary environment: How to convert soft-dollar assets like Treasury bills into hard-dollar assets to inoculate it, amongst other things, against the possibility of future inflation.

The two countries need a more solid economic grand bargain, a new framework that puts an end to this dilemma once and for all.

There is a fairly obvious exchange that aligns China's needs to protect its reserves with America's need to reduce its debt while renovating its infrastructure. China would over time redeem its holdings of U.S. debt into a more protected stake in U.S. infrastructure providing the crucial capital to rebuild its rival.

Instead of China recycling its trade surpluses into the more risky tasks of building its neighbors in Asia, and investing in Latin America and Africa, why not recycle that money into America's $3 trillion infrastructure deficit?

One is still left with the reality that there is strong resistance in the U.S. to the Chinese investing in our infrastructure. In part, this is based on a misunderstanding. This effort would not require the selling of state assets outright or the elimination of state control or ownership of them, all of which are political non-starters. More than enough capital can be raised by soliciting minority equity positions or long-term debt that unlike treasuries can't be sold at the investor's whim. Countries like Australia have long shown it is possible to secure long-term capital from China for infrastructure without abdicating control.

Still, breaking through U.S. resistance will require the Chinese to adopt a more proactive posture, as they have elsewhere in the world. Here is their playbook: First, they announce with great fanfare their goals for total investment in a particular continent. Next, they wait for individual countries within the continent to compete for the fixed pool of capital allocated to that continent, in effect creating a beauty contest.

There is no reason China couldn't create a similar dynamic in America thanks to our federal system. If New York isn't interested in their money, they still have 49 other choices. It just requires the same type of bold, upfront commitment China has made elsewhere.

A five-year, half-trillion-dollar commitment to American infrastructure, by inviting follow-on capital from other sources, could be the quickest path to a middle-class job bonanza in the United States. It would begin the process of changing U.S. public opinion toward China, with China being viewed increasingly as a job creator, not a destroyer. It would act as a bridge until China's middle class takes its rightful place and is able to pull its own weight in the international trading system.

That commitment is of course much more likely to happen if the federal government signals its openness to such a policy. President-elect Trump is a builder who has already said revamping our infrastructure is going to be a top priority. He has also stated he is committed to fixing the balance sheet of America by reducing our $20 trillion treasury debt. And one of his signature promises--to win back middle-class jobs from China--is more likely to be accomplished by welcoming Chinese capital for our infrastructure than by naming China a currency manipulator on day one, a much more risky policy that in any case was more suited to circumstances a decade ago.

Most significantly, by moving the needle on public opinion, it could open up the floodgates for resolving our other pressing issues with the Middle Kingdom.

"History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes," or so said Mark Twain. How ironic would it be if a U.S. president who had built his political reputation on strident opposition to China turned out to be the one who achieved the most consequential breakthrough in bilateral relations since another China foe, Richard Nixon, made his epic trip to Beijing in 1972.